Purpose:

Hodden Grey: From Scottish Homespun to Modern Battledress (2022) reintroduces the knowledge of Hodden to the Scottish diaspora to partner the more well-known tweed and tartan Scottish fabrics. This book attempts to show that they are progressively more complicated patterns developed from the much earlier lachdann and lachtna.

- Why is it ‘hodden grey’ in the Scottish lexicon?

- What do we know of early Celtic textiles?

- What were the early Gaelic customs on peasant dress?

- What were the medieval Scottish Sumptuary laws?

- What does ‘hodden‘ mean?

- Why is ‘hodden grey’ considered a tartan?

- Why is hodden grey so little known?

©Copyright 2022 Anthony Partington. All rights reserved.

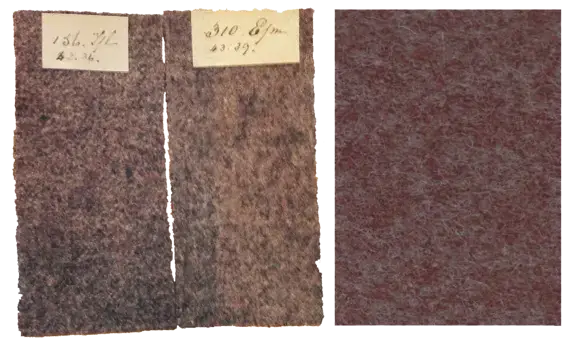

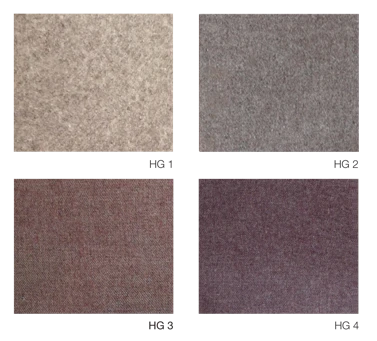

The four Hodden Greys of the London Scottish

HG 1. Dun-coloured commercial hunting tweed, originally from Lord Elcho’s deerstalking coat, 1860—c. 1867.

HG 2. Hodden Grey Government pattern, c. 1867—95.

HG 3. 'Heather-Brown / Ruadh’ Hodden Grey, c. 1895—1939.

HG 4. ‘Plum tones’ Hodden Grey, c. 1939—2022.